Triple-A gaming is failing our generation

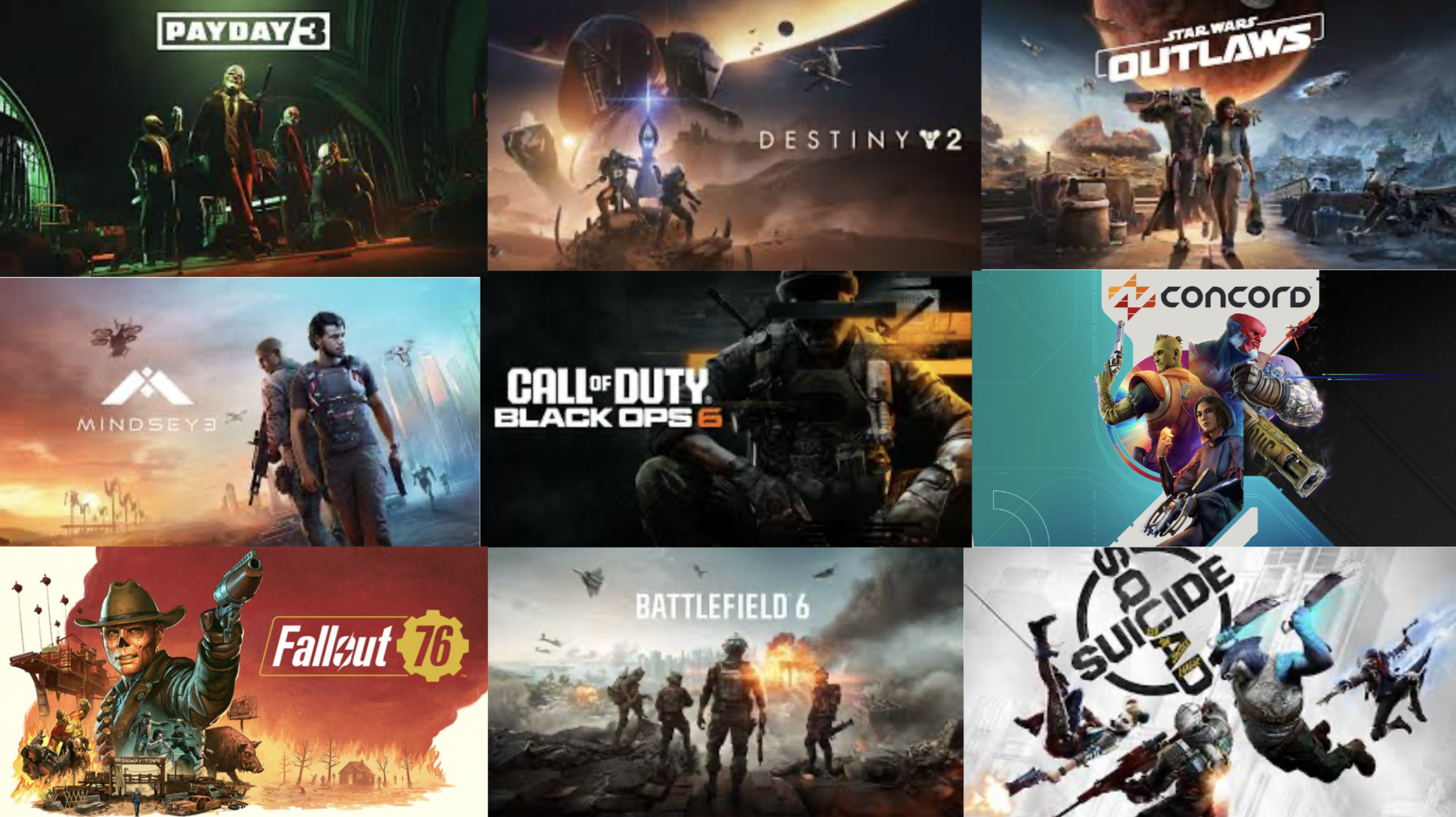

Canva image featuring Triple A Video Games that contributed to the downwards trend of Triple A in the industry. (Chase Soylu Chee / The Puma Prensa)

By Chase Soylu Chee, News Editor & Video Editor, and Staff Writer Logan Budlong

It is the early 2000s, and famous video game franchises like Call of Duty and Halo keep making better games with each new release, while other masterpieces like Grand Theft Auto V and Black Ops III are also coming out. Times have changed, and the once-great Triple-A industry has fallen out of public grace.

Triple-A gaming is a term used to describe major studios, productions, or corporations that release video games. It has been directly correlated with the famous corporations such as Electronic Arts (EA), Blizzard, Activision, Ubisoft, Bungie, and many others.

Pinning down exactly what started this is hard; seeing the major influences is not. Appeasing investors and the “pump and dump” scheme of producing games and cutting to the bare bones to save profits is just the tip of the iceberg.

Microtransactions

The first plague that infected the industry was microtransactions. From the $0.99 microtransactions for in-game cash to buying permanent characters for $5.99 transactions in Triple-A gaming has gone a long way. This was a way for games to continue to get revenue from existing players, which was reasonable in the past to support the series’ growth.

Over time, individuals with poor spending habits could outweigh their skill by spending balances on their credit cards on in-game purchases. Games that involved skill and a PVP (Player vs. Player) environment took note of this and implemented pay-to-win features, another deadly spiral.

The most notable to implement this strategy was Supercell’s Clash Royale, which overtook its competitors. It’s a fast-paced mobile strategy game where players collect cards that represent troops, spells, and buildings, then use them in battles to receive crowns by destroying their opponent’s towers. Cards in Clash Royale are collected through chests that you get by winning matches. Users can use gems (premium currency) and coins to level up cards, buy chests, and emotes from the in-game shop.

Slowly, Supercell added deals that boosted players’ progress in leveling up and gathering cards. Then, one deal became two, and over time, four; this exponential growth made the in-game store more of a deal shop than a place to use coins for daily cards.

Screenshot of Clash Royale's Evolution and Legendary Market. (Chase Soylu Chee / The Puma Prensa)

Taking advantage of this, the Finnish corporation pushed out updates that added new cards that raised the bar of progression and skill to new heights every month. To get ahead, players had to start constantly spending money on packs.

Because it is a competitive game, taunting with emojis became popular online, and with that brought emojis of in-game characters taunting opponents. This saw a spike in popularity after streamers and players raged while being beaten and taunted.

Clash Royale Influencers featuring Streamers Jynxzi & Juicy and Clash Royale Top Players Ryley & Mohamed Light. (Courtesy of Juicy - Clash Royale)

Finally, around the end of 2025, the community was on its last straw. With a heightened popularity and influence online, the corporation added a whole new card level and card type called “Heroes.” Adding four new cards, which broke the skill gap, made it easy to beat opponents with a singular card. This enraged the community, but the corporation addressed these claims by making it accessible for people who didn’t want to pay.

The Hero event that was integrated in the update allowed players who participated to get one random hero from the pool of four that had been created. However, what fans soon discovered was that Supercell had changed things behind the scenes to ensure players would still end up spending money.

The four heroes that were made were not created equal, as most free-to-play players got the hero giant which was the most undesirable in sales. Supercell knew that giving most free-to-play players the worst card would increase the chances of them buying the desirable cards, such as the hero knight.

Lastly, adding more collectable overpowered cards with every update, which makes a serious change in strategy during a match, makes the game more unfair for players who do not spend money. This is because people who spend money get access to cards that are usually unbalanced on release, resulting in an uptick in losses for people who do not spend money at the start of every season.

Season & Battle Passes

Another famous money maker used by Supercell, which promoted spending and transactions in-game, was the Season Pass, made popular by EpicGames’ most famous video game: Fortnite.

Most referred to as Battle Passes, they are one-time purchases at every “Season” of a game; players buy a pass to about 100+ in-game items, which are earned by either completing objectives and missions or by simply playing the game and getting experience points. By the start of the next season, players would have to buy another pass and complete the next challenges, as each pass would have exclusive items for that season only.

In Fortnite, the infamous pioneer of the Battle Royale genre, 100 players are dropped on a map fighting to the death to be the sole survivor of the match. Fortnite was revered for its revolutionary building mechanic that introduced another skill curve, adding an extra level of achievement and satisfaction after playing.

Fortnite pioneered the battle pass perfectly, making it give back your money and offering in-game accessories if you completed it. This made players happy because you could buy one battle pass and use that money, plus extra, to get the next battle pass and anything you wanted in the store. promoting player saving and less spending for people hesitant to spend money.

Within the battle pass, there were free collectables, allowing free-to-play players to buy the battle pass for free after completing three seasons’ worth of passes. Historically, in season eight, a questline was given for players to receive a pass for free.

While Fortnite made the battle pass accessible and achievable for everyone, regardless of spending, making the game solely dependent on skill was perfect until other studios decided to make this praised feature a money-making opportunity.

An example of this is Destiny 2, a widely popular live service science fiction shooter, whose battle pass is an example of corporate greed; however, like many live service games, the battle pass was integrated into the game in 2019 after it was demonstrated by Fortnite how profitable the idea could be.

Unlike Fortnite's early battle passes, however, the price-to-return ratio was not there, with the rewards only being in-game consumables and cosmetics with no currencies that could be used in future battle passes or in the in-game store. Additionally, the battlepass was made to promote a fear of missing out, as the cosmetics used often never return and were only attainable if you purchased the extra reward track.

Going public and investor impacts

To go above and beyond making money, companies need corporate investors to fuel adventures that play in the gaming industry in their favor. The result: going public on the stock market and having investors influence decisions and developments, which has proven not to be a good idea.

With investors, games often have larger budgets and more hands working on them; however, this comes with profit margins and time limits put in place to keep the investors happy. As investors demand a return on their investment by a certain date, companies rush their products and shove them full of microtransactions in the hopes of making more money.

This puts off the consumers who look forward to enjoying a polished game from their favorite game developers, but instead find a mess of greed and cut corners, resulting in the games often performing poorly. Studios such as Electronic Arts (EA) have had their image run into the ground by investors who keep demanding they get their money, turning the studio into a greedy mess of monetization.

Many expansions into EA’s portfolio, such as Star Wars Battlefront II, their sports games, and The Sims 4, were many of the games that had greedy monetization efforts due to investors. Starting with the Star Wars shooter, Star Wars Battlefront II, there was an aggressive loot box system and pay-to-win mechanics that allowed players to get ahead in a game about skill.

Photo of Star Wars Battlefront II Trooper Crate loot box. (Business Insider)

With the sports games such as FIFA that EA owns, every year there's a new game, but there is a heavy reliance on microtransactions. With every new installment looking just like an update, the most notable changes are new players and teams that can be used. It is more evident when most of their newer sports games have a “Mixed” rating on Steam, which means the game has a 40% to 69% rating from the community playing it.

Lastly, with The Sims 4, the series that pioneered life simulation games, their fourth game had dozens of DLCs costing more than one thousand dollars, with content split to maximize as many sales as possible.

On September 29, 2025, the Public Investment Fund, Silver Lake Partners, and Affinity Partners bought out Electronic Arts for $55 billion. After being bought out by mostly Saudi Arabian investors, the company became privately owned, meaning investors did not have a chokehold on game production anymore.

(EA announced that creative decisions and game development will remain under their control.)

Conclusion

With the continued expansion of the video game industry, the impacts of monetary transactions and predatory decisions have only become more of a focus for gamers everywhere. Now, a game is not weighed based on its graphics first, or even its story and gameplay, but whether or not the company's reputation is poor, and if the game has microtransactions baked in.

As the market grows, so do its flaws. Triple A gaming has locked itself into a cycle it can no longer escape, prioritizing monetization over substance. As formulaic releases pile up, players are quietly turning away from name-brand titles and towards indie games made up of blood, sweat, and tears. Projects like Ark Raiders, Hollow Knight Silksong, and many other popular independent titles signal this ever-growing shift towards the community instead of profits.